Good Management Part II: The Complexity Fallacy

Why The Arsonist Is Rarely The Right Firefighter

(This post is a continuation of the themes we explored in our Bengal Catalyst Fund Q2 2023 letter)

The Complexity Fallacy

As the markets unraveled in 2008 the world was left wondering what exactly was going on within our financial institutions? As the layers were peeled back, the state of their balance sheets revealed themselves to be an unprecedented mess of interconnected complexities. These extreme situations are usually novel in nature and lead us into uncharted waters (otherwise by definition they would have been solved beforehand and wouldn’t have been allowed to become “extreme”).

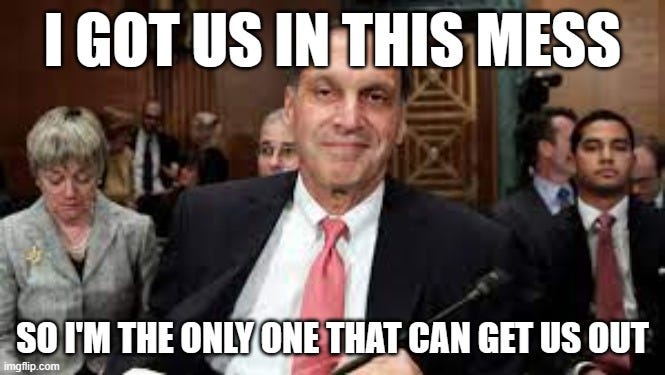

The world of finance has seen many bank failures, malfeasance, etc. over the past centuries - so there is a deep bench of third-party experts in how to solve these issues when they occur. Even still, the 2008 crisis was unprecedented in its scale and complexity for even the most seasoned banking experts. In times such as this - what sometimes occurs is what we term the “Complexity Fallacy.” This happens when a mess is so extreme and unique that no one on the outside can credibly claim they know how to navigate the situation. What happens next is that advisors, boards, and even government officials are forced to take the advice of the only people who sound intelligent on the matter…these usually end up being the people who caused the situation in the first place. Who better to tell you how disastrous a house of cards is than the architect and builder of that exact house?

The problem with this line of thinking is that the alignment of incentives between existing management and investors for cleaning up poor decisions is often at odds. It reminds us of the lyrics in Taylor Swift's “Anti Hero”: I’ll stare directly at the sun but never in the mirror. Having to admit and atone for the past mistakes of your own doing and unwinding the very decisions that caused the mess you find yourself in is very hard. Tough situations call for hard decisions that need to be made with the future in mind - not relitigating and justifying the past.

As Applied to Cannabis Today

What does any of this have to do with cannabis? Part one of our last post included as part of our 2Q update for our LPs was a thought exercise on what constitutes “good management” of a company. We strongly believe capital allocation (and, more holistically, resource allocation) is at the top of that list. A very close second is accountability. Thus far in these early innings of cannabis there has been very little in terms of accountability. We’re not here exclusively to point fingers. This industry has not played out exactly like anyone thought but, even so, some of the mistakes made should have been prevented based on sound business judgment alone. We have certainly made mistakes and are very introspective and open when we make them. But there needs to be a cost imposed for those who make mistakes. Without accountability for past blunders what is the incentive to change decision making?

Cannabis especially has seemed prone to “herding” among large MSO management teams and boards - they have often mirrored each others’ mistakes and later attempted to justify those mistakes by all pointing at everyone else. Shareholder losses from managements’ decisions to enter markets they are not prepared to compete in are chalked up to “bad markets” rather than poor decisions. In our view, other investors have been far too credulous of post hoc justifications. Investors seem to accept many explanations for why those in the cannabis herd frequently make the same mistakes except for the most glaringly obvious: it’s just not a very good herd.

Unlike other industries, there aren’t “experts” a distressed cannabis company can bring in to turn around operations. Even worse, many cannabis company boards are made up of high profile individuals with zero cannabis industry experience. In those situations, it's very difficult for a board to speak out against current management. They’re beholden to the information being given to them internally and don’t have nearly the industry knowledge needed to push back when mistakes are made.

Imagine you spent your life as a salesman at an insurance company. Say you’re the best salesman that company ever had. You rise to the level of CEO of that insurance company and lead their sales team for years and years. Now imagine your resume gets noticed and you are appointed to be on the board of directors at a successful biotech start up. You know nothing of the industry and have never spent any time in it. Suppose this biotech company has an experimental drug in the pipeline that they’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars on. In that situation - would you honestly be able to ask pertinent and reasonable questions about how the drug development was coming along? Would you be able to process whether money was being spent wisely or efficiently? In almost every angle of this scenario the answer is no. You would listen to the management team reporting to you (the “experts”), and find it incredibly hard to push back on anything they were saying (“Who am I to question doctors and scientists who have been in this field for 20 years?”). This creates the wrong feedback loop for governance and only exacerbates the “Complexity Fallacy.”

What the World Needs Now Is…

What cannabis needs is real governance that can hold management teams accountable for their actions. It’s easier said than done and in many cases it threatens the iron grip that founders and current management have on their boards. But, if true institutional capital were to ever enter the space, this dynamic needs to change. It may be a tough pill for some companies but the entire ecosystem will be better off once the medicine is administered. True governance and accountability would actually be a real reason to assign premium multiples for a company.

100% agree. How do we get real fiduciaries on these boards? Do we have to wait until they're traded in NY and hedge funds and activists push for change? If so can the companies survive until then?