Dear Investor,

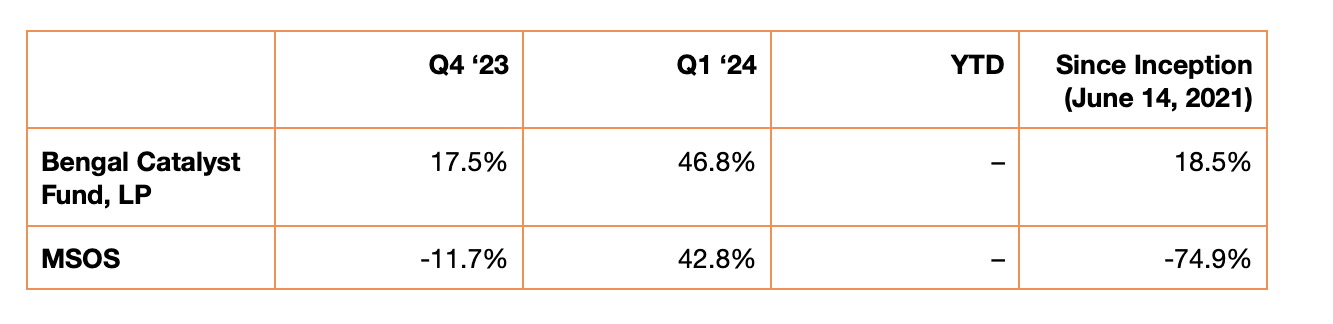

The Bengal Catalyst Fund, LP’s (the “Fund”) performance (preliminary estimates, net of fees, and unaudited) is presented below alongside that of MSOS, a US cannabis-focused ETF. We do not consider MSOS a benchmark, but we do believe it is the closest equity market proxy for the US cannabis industry, so we view it as a reasonable indicator of cannabis investor sentiment.

*Note that the above figures net out our current estimate of incentive allocation for Q1 2024. The final numbers may be slightly different from what we estimate, but hopefully not materially so. We expect to have final numbers issued by our fund administrator soon.

As we mentioned in our 2023 year end fund letter, the Fund had a strong start to 2024 and that strength continued through the end of Q1 2024. The Fund is now comfortably positive since inception and, somewhat surprisingly given the industry’s performance, also ahead of the S&P 500. We are proud of this, but feel compelled to continually remind our investors that this industry comes with high volatility. Our focus, as from the start, is on how we feel the intrinsic value is developing in our portfolio in the medium to long term - and we continue to be happy with that trajectory.

A few reminders:

Your results may vary from those above depending on time of investment

The above figures do not include the results of any side pockets

We expect our returns to be volatile given the illiquidity and concentration of the Fund’s portfolio. Regarding the last point, we fully expect that there will be periods in which we underperform the broader cannabis equity market as we seek to generate sustainably better longer term returns.

Your individual account statements should be available soon at the current fund administrator’s (Panoptic) investor portal. Please reach out to us if you need help accessing them.

As is our usual practice, we are sharing some thoughts regarding the cannabis investment environment below as well.

Bengal Commentary - Q1 2024

Vertical Limit

But First, No Message from the DEA

Right before this letter was about to be sent out, another story hit presses: that the DEA’s schedule 3 recommendation was now currently sitting with the Office of Management and Budget for a final review before publishing. The story did not actually contain any official DEA statement, but it appeared to be well sourced with at least five anonymous sources confirming the essentials. Cannabis stocks went up, then down, and are now modestly above previous levels.

In terms of publicly visible, official indicators of rescheduling progress, the DEA has not taken any apparent action on the HHS recommendation that it received in August 2023. Investor expectations seem to be that any official DEA Schedule 3 recommendation would be the culmination of a long journey, which it may be for the purposes of public markets. But, legally, it is a bit closer to the middle - any official recommendation kicks off a process that would likely take over a year to finish. Hopes of a final rescheduling being completed before this year’s election seem faint. If cannabis history is anything to go on, long legal processes create volatility until they are finally resolved, even if most agree on what the final result will ultimately be.

Commentators have frequently compared the timeline of cannabis’ current potential rescheduling to those of other substances - first to set expectations on how long a cannabis rescheduling process could take, and now mostly to show how unexpectedly long it is taking. Investors should not expect a typical rescheduling process in an atypical situation. That some of those reschedulings involved derivatives of cannabis that had been turned into pharmaceutical products does not change anything - we should all be able to look in the mirror, admit that the rescheduling of cannabis is a big deal politically, and set our expectations accordingly.

Or, better yet, just look for situations where rescheduling is a nice bonus but not necessary to profiting as an investor.

Sacred Cows and Milk

As cannabis markets mature, prices fall and units sold rise. As we discussed in our last letter regarding Michigan specifically, simply saying cannabis markets are “growing” misses two underlying cross currents: average sales prices fall while units sold grow more than enough to make up the shortfall leading to a “bigger” market, albeit one with less profit per unit sold. This dynamic has started to increasingly become reflected in exactly where investors should expect to see it: large MSO gross margins have been trending down as prices fall. These large MSOs, which are dependent on investors’ perceptions of continuing outsized profitability, often “lean in” to their vertical integration to “protect” their margins. Some large MSOs even have started to disclose what percentage of their retail sales are vertical (i.e. product which they produce themselves) - Curaleaf disclosed 63% of its 2023 retail sales were vertical and Cannabist was over 50%, although both numbers are likely somewhat inflated by inclusion of Florida sales, where vertical integration is de facto required rather than being a business decision. Ayr reported 44% excluding Florida, seeming to regretfully admit that this was down from their previous 50% mark.

That “leaning in” to vertical integration augments profits does not seem to be seriously doubted by investors or analysts. Rather, it is a bit of an unquestioned sacred cow. But this thinking fails to recognize when and why vertical integration is useful in cannabis and, in doing so, fails to recognize when “leaning in” to vertical integration is actually a recipe for long term disaster.

When Vertical Integration Does and Does Not Matter

Let’s take a step back and imagine you are a dairy farmer who owns one (sacred) cow Bessie, one retail milk store called Corova. Reliable Bessie produces one gallon of milk per week which costs you $3 all-in. When that gallon of milk is produced, you have two choices: you can sell it into the well established wholesale market for $6 per gallon, or you can transfer it and sell it at the Corova for $12 per gallon.

To most, the analysis seems to end right here - of course you transfer it to your store since you make $9 instead of selling it wholesale and only making $3. But this forgets the other possibility in well-functioning markets, as silly as it might seem in this hypothetical: you can always sell your milk at wholesale for $6, then buy someone else’s wholesale milk at $6 and sell that milk in your store for $12 and make the same total $9 profit. So, assuming a well-functioning wholesale market in this example, you (the dairy farmer) don’t really care too much about selling your milk vertically or horizontally - you make the same amount of money either way.

In cannabis, vertical integration in limited license markets often is initially very important precisely because there is no well-functioning wholesale market - if you didn’t have Bessie in this kind of market, you just wouldn’t be able to sell any milk at the ol’ Corova, and you’d earn nothing. In these markets having your own production is critical. This is one of the primary reasons why we support, for example, Grown Rogue’s careful expansion into supporting retail in New Jersey - a store with products to sell in early markets makes all the sense in the world. As nascent markets mature, vertical integration often becomes important for a different reason: too much product at wholesale instead of not enough.

Going back to the dairy farmer example: Let’s imagine that there’s an overproduction of milk across the country and that Bessie’s milk can no longer be sold at wholesale since there’s just no demand for it at any price because everyone has plenty of milk. But retail customers are still chugging down gallons of milk at the Corova, so you just transfer Bessie’s milk to your store and keep making your profits regardless of what the wholesale market is doing. All in all, a good strategy that protects you from the oscillations of the wholesale market - and one many large MSOs claim to be currently “leaning into.”

Let’s say that instead of there being zero demand for Bessie’s milk, there is some demand but not at the prevailing market price of $6. You see, Bessie only produces skim milk and everyone knows skim milk is basically water with white food coloring added so they won’t pay $6 for Bessie’s milk - they’ll only pay $5. As an angry dairy farmer not wanting to admit that Bessie produces anything other than mids milk, you ignore the wholesale offer of $5 and instead sell it through the Corova for full price. Who cares if the wholesale market tried to lowball you when you got to lean into verticality and keep your margin? To an investor in your dairy farm, the financial statements from the first scenario and second scenario initially look pretty much the same. Your sales and margin remain stable - all is well with Bessie and the Corova. This is the reality of what many large MSOs are doing: selling their subpar products at par (or higher) prices.

When Leaning In Goes Wrong

What happens next has been shown since the start of free markets, and in mature cannabis markets specifically: sooner or later your customers notice that they are getting a bad deal and go elsewhere. In the real world, signals are muddied - in cannabis companies even more so as their financials are often an undifferentiated mix of mature and nascent states along with everything in between.

Eventually, the signs become much more pronounced as what happens is pretty much exactly what economic theory would predict: unsold inventory accumulates as sales trim down but margins seemingly stay consistent - some really bad inventory even gets written off completely. So far the solution for this among large cannabis companies has been not to admit or fix the underlying problem, but instead drop prices to clear inventory while crowing about “generating cash” and/or adjusting out the inventory writeoffs and focusing on the “adjusted” gross profits. The reality of financial statements also drives MSOs behavior because dropping prices and margins are immediately evident in financial statements, but missing sales from customers walking away rather than purchasing are much harder to see.

While a good strategy for starting markets, a focus on vertical integration in later markets by large MSOs should be realized for what it is: limiting consumer choice as a way of pushing them towards favored products which would not be able to fetch the same prices if sold through a different channel. Not serving your customers well creates negative compounding, even if the effects are delayed and difficult to see immediately in the financial statements, which pulls down the future value of the company. So, by “leaning in” to verticality to “protect” margins, many large MSOs are destroying future value by either sacrificing retail store profits to save wholesale profits or vice versa.

What We Are Not Saying

We are not saying vertical integration is always bad, or always doesn’t work, or anything else like that. A well run store and a well run production facility can both exist together without any issues - the problems with vertical integration appear when one business starts to be used to support the other business rather than being maximized in its own right. Using a store to shore up a bad production facility ultimately hurts more than it helps as the store eventually gets dragged down as well. Many MSOs seem to be only thinking backwards from what they think investors want (higher gross profits, aEBITDA margins, or whatever) and losing even any pretense of starting from what their customers want.

Being a Low Cost Producer Changes Things a Bit

Generally, high prices have driven most cannabis industry cashflow thus far. Industry players all seem to pay lip service to the idea that prices will at some point go down, but then they continue to push narratives that fundamentally amount to “We can sell in state X in early adult use where cannabis will be going for $6,000 per pound.” So how do cannabis companies make profits when prices come down?

In mature markets, we believe being a low cost producer of the respective quality tiers of products is a prerequisite for long-term success, with perhaps some boutique producers/brands able to buck that reality. This does not necessarily mean being the absolute low cost producer (e.g., the lowest cost per gram outdoor feedstock grower), but it does mean that for whatever class of product you are selling (e.g., craft-quality indoor cannabis), your costs should be the lowest cost in the industry for that class of product. Being a low cost producer combined with a retail portfolio allows a company to run a version of the same playbook run by Amazon so successfully: sharing savings with your customer in the form of lower prices, and therefore lower nearterm profits, in order to build outstanding customer loyalty and higher profits in the long term.

So, as a low cost producer, we do see the opportunity for an augmented retail portfolio, albeit we think it’s important to be sensible of the channel conflict, so as to not put the wholesale business at risk. But, this is not so much an endorsement of verticality as it is an acknowledgement of the inherent protections to being a low cost producer period. And, suffice it to say, we do not see this kind of strategy being pursued by any of the large MSO players, which are still focused on having high prices for as long as possible.

Cannabis is Not iPhones

When it comes to vertically integrated companies, the quickest to mind is generally Apple. Pushing into its own retail stores was revolutionary at the time. Microsoft followed suit only to quietly close their stores a few years later. People are loathe to give up their sacred cows generally, so we imagine that one of the objections to what we wrote above is to point to some ephemeral supposed benefits of being vertical - our guess is that invariably Apple will come up as an example, despite the abject failure of at least MedMen to copy Apple’s playbook. Without delving too deeply into it, suffice it to say that buying an iPhone for close to a thousand dollars is a little bit different than deciding on a $25 eighth, and the industrial logic of how an industry is organized and whether vertical integration is or is not a benefit follows accordingly.

Another supposed successful vertically integrated model sometimes used as an example for cannabis companies to follow is Trader Joe’s. Somehow, this manages to be an even worse metaphor for the cannabis business than Apple. We imagine most people who have used this example do not realize that Trader Joe’s doesn’t actually make its own branded products, instead outsourcing to manufacturers - in other words, doing exactly the opposite of vertical integration of production facilities.

Chicken Salad Vs. Alternatives

In an ideal world, vertical integration can be excellent because it allows a more direct signal from customer to production. Customers tell you what they want daily and the production facility can continue to hone in on those wants with no middle man. This is largely not what is happening in practice within the cannabis industry. Especially humorous are companies which tout having mountains of “data” on what their customers supposedly want based on those customers’ previous purchases. This is like looking at the fact that people only bought black Ford Model Ts and concluding that no one will ever want a car in any other color without realizing that the Model T was only offered in black. In markets with minimal product assortment, low differentiation, high prices, and a relative lack of competition, this kind of “data” is not particularly useful in predicting what customers will do when given real choices.

Instead, large MSOs are leveraging the minimal current competition that limited license retail networks provide to force customers to purchase something which that MSO makes instead of something the customer really wants. Maybe, frankly, the customer doesn’t even know what they want yet - maybe what is par product in their market is subpar in a more mature market. But, in time, even limited license markets become competitive enough that customers start to understand what’s what. Again, as Jeff Bezos has reminded us: Customers figure these things out. Any long term strategy that depends on your customers forever not understanding the difference between chicken shit and chicken salad is doomed to failure.

As usual, we believe this supports the higher quality little guys in the industry like Grown Rogue, which make customer value a cornerstone of everything they produce. Given how much of cannabis consumption does take place in the value segment, a strategic lowest cost producer of THC potentially also stands to benefit long term from these dynamics.

Many industry watchers see current large MSOs market shares as set in stone without giving any credence to the possibility that smaller players can take meaningful share in the long term, but we believe that this is exactly what will happen as the compounding of giving customers what they want meets the negative compounding of giving customers what MSOs want them to want.

-

Should you wish to respond to this letter or discuss anything within it, please reach out to Bengal partner Jerry Derevyanny at jerry@bengalcap.com. We are always happy to thoughtfully engage with those that agree and disagree with us.

Disclaimer

The information contained in this letter is provided for informational purposes only, is not complete, and does not contain certain material information about our Fund, including important disclosures relating to the risks, fees, expenses, liquidity restrictions and other terms of investing, and is subject to change without notice. This letter is not a recommendation to buy or sell any securities.The information contained herein does not take into account the particular investment objective or financial or other circumstances of any individual investor. An investment in our fund is suitable only for qualified investors that fully understand the risks of such an investment after reviewing the relevant private placement memorandum (“PPM”). Bengal Impact Partners, LLC (“Bengal Capital” or “we”) is not acting as an investment adviser or otherwise making any recommendation as to an investor’s decision to invest in our funds.

Perhaps most importantly, Bengal Capital has no obligation to update any information provided here in the future, including if any positions discussed are sold or purchased, or if different positions are purchased.This document does not constitute an offer of investment advisory services by Bengal Capital, nor an offering of limited partnership interests of our Fund; any such offering will be made solely pursuant to the Fund’s PPM. An investment in our Fund will be subject to a variety of risks (which are described in the Fund’s definitive PPM), and there can be no assurance that the Fund’s investment objective will be met or that the fund will achieve results comparable to those described in this letter, or that the fund will make any profit or will be able to avoid incurring losses. As with any investment vehicle, past performance cannot assure any level of future results.We make no representations or guarantees with respect to the accuracy or completeness of third party data used or mentioned in this letter. We provide services, such as strategic consulting services, to certain entities mentioned in this letter and may in the future provide such services to more in the future, or to companies not mentioned in this letter. While we may sometimes advise on issues regarding corporate communications, we do not believe any of the services which we provide are “stock promotion” - we have not been and will not be compensated for the mention or discussion of any of the companies discussed herein. We disclose such arrangements to investors in the Fund and will continue to do so.